Diet Aloha-energy Drink Syrup

Beverage containing stimulants

Various brands of energy drinks

An energy drink is a type of drink containing stimulant compounds, usually caffeine, which is marketed as providing mental and physical stimulation (marketed as "energy", but distinct from food energy). They may or may not be carbonated and may also contain sugar, other sweeteners, herbal extracts, taurine, and amino acids. They are a subset of the larger group of energy products, which includes bars and gels, and distinct from sports drinks, which are advertised to enhance sports performance. There are many brands and varieties in this drink category.

Coffee, tea and other naturally caffeinated drinks are usually not considered energy drinks. Other soft drinks such as cola may contain caffeine, but are not considered energy drinks either. Some alcoholic drinks, such as Buckfast Tonic Wine, contain caffeine and other stimulants. According to the Mayo Clinic, it is safe for the typical healthy adult to consume a total of 400 mg of caffeine a day. This has been confirmed by a panel of the European Food Safety Authority, which also concludes that a caffeine intake of up to 400 mg per day does not raise safety concerns for adults. According to the ESFA this is equivalent to 4 cups of coffee (90 mg each) or 2 1/2 standard cans (250 ml) of energy drink (160 mg each/80 mg per serving).[1] [2]

Energy drinks have the effects of caffeine and sugar, but there is little or no evidence that the wide variety of other ingredients have any effect.[3] Most effects of energy drinks on cognitive performance, such as increased attention and reaction speed, are primarily due to the presence of caffeine.[4] Other studies ascribe those performance improvements to the effects of the combined ingredients.[5] Advertising for energy drinks usually features increased muscle strength and endurance, but there is no scientific consensus to support these claims.[6] Energy drinks have been associated with many health risks, such as an increased rate of injury when usage is combined with alcohol,[7] and excessive or repeated consumption can lead to cardiac and psychiatric conditions.[8] [9] Populations at risk for complications from energy drink consumption include youth, caffeine-naïve or caffeine-sensitive, pregnant, competitive athletes and people with underlying cardiovascular disease.[10]

Uses [edit]

Energy drinks are marketed to young children and provide the benefits among health effects of caffeine along with benefits from the other ingredients they contain.[11] Health experts agree that energy drinks which contain caffeine do improve alertness.[11] The consumption of alcoholic drinks combined with energy drinks is a common occurrence on many high school and college campuses.[12] The alcohol industry has recently been criticized for marketing cohesiveness of alcohol and energy drinks. The combination of the two in college students is correlated to students experiencing alcohol-related consequences, and several health risks.[12]

There is no reliable evidence that other ingredients in energy drinks provide further benefits, even though the drinks are frequently advertised in a way that suggests they have unique benefits.[11] [13] The dietary supplements in energy drinks may be purported to provide produce benefits, such as for vitamin B12,[11] [14] but no claims of using supplements to enhance health in otherwise normal people have been verified scientifically. Various marketing organizations such as Red Bull and Monster have described energy drinks by saying their product "gives you wings",[15] is "scientifically formulated", or is a "killer energy brew".[11] Marketing of energy drinks has been particularly directed towards teenagers, with manufacturers sponsoring or advertising at extreme sports events and music concerts, and targeting a youthful audience through social media channels.[16] There is some evidence that L-Theanine, a compound found in some energy drinks, has positive effects on mood, anxiety and cognitive function; the effects are more pronounced in conjunction with caffeine.[17] [18]

When mixed with alcohol, either as a prepackaged caffeinated alcoholic drink, a mixed drink, or just a drink consumed alongside alcohol, energy drinks are often consumed in social settings.

Effects [edit]

A health warning on a can of the Austrian Power Horse energy drink

Energy drinks have the effects caffeine and sugar provide, but there is little or no evidence that the wide variety of other ingredients have any effect.[3] Most of the effects of energy drinks on cognitive performance, such as increased attention and reaction speed, are primarily due to the presence of caffeine.[4] Advertising for energy drinks usually features increased muscle strength and endurance, but there is little evidence to support this in the scientific literature.[6]

A caffeine intake of 400 mg per day (for an adult) is considered as safe from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA).[2] Adverse effects associated with caffeine consumption in amounts greater than 400 mg include nervousness, irritability, sleeplessness, increased urination, abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmia), and dyspepsia. Consumption also has been known to cause pupil dilation.[19] [ medical citation needed ] Caffeine dosage is not required to be on the product label for food in the United States, unlike drugs, but most (although not all) place the caffeine content of their drinks on the label anyway, and some advocates are urging the FDA to change this practice.[20]

With alcohol [edit]

Combined use of caffeine and alcohol may increase the rate of alcohol-related injury.[7] Energy drinks can mask the influence of alcohol, and a person may misinterpret their actual level of intoxication.[21] Since caffeine and alcohol are both diuretics, combined use increases the risk of dehydration, and the mixture of a stimulant (caffeine) and depressant (alcohol) sends contradictory messages to the nervous system and can lead to increased heart rate and palpitations.[21] Although people decide to drink energy drinks with alcohol with the intent of counteracting alcohol intoxication, many others do so to hide the taste of alcohol.[22] However, in the 2015, the EFSA concluded, that "Consumption of other constituents of energy drinks at concentrations commonly present in such beverages would not affect the safety of single doses of caffeine up to 200 mg." Also the consumption of alcohol, leading to a blood alcohol content of about 0.08%, would, according to the EFSA, not affect the safety of single doses of caffeine up to 200 mg. Up to these levels of intake, caffeine is unlikely to mask the subjective perception of alcohol intoxication.[2]

Health problems [edit]

Excessive consumption of energy drinks can have serious health effects resulting from high caffeine and sugar intakes, particularly in children, teens, and young adults.[23] [24] Excessive energy drink consumption may disrupt teens' sleep patterns and may be associated with increased risk-taking behavior.[23] Excessive or repeated consumption of energy drinks can lead to cardiac problems, such as arrhythmias and heart attacks, and psychiatric conditions such as anxiety and phobias.[8] [9] [23] In Europe, energy drinks containing sugar and caffeine have been associated with the deaths of athletes.[25] Reviews have noted that caffeine content was not the only factor, and that the cocktail of other ingredients in energy drinks made them more dangerous than drinks whose only stimulant was caffeine; the studies noted that more research and government regulation were needed.[23] [26]

Research suggests that emergency department (ED) visits are on the increase. In 2005, there were 1,494 emergency department visits related to energy drink consumption in the United States; whereas, in 2011, energy drinks were linked to 20,783 emergency department visits.[27] During this period of increase, male consumers consistently had a higher likelihood of visiting the emergency department over their female counterparts.[27] Research trends also show that emergency department visits are caused mainly by adverse reactions to the drinks. In 2011, there were 14,042 energy drink-related hospital visits.[27] Misuse and abuse of these caffeinated drinks also cause a significant amount of emergency department visits. By 2011, there were 6,090 visits to the ED due to misuse/abuse of the drinks.[27] In 42% of cases, patients had mixed energy drinks with another stimulant, and in the other 58% of cases the energy drink was the only thing that had been consumed.[28] Several studies suggest that energy drinks may be a gateway drug.[7]

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children not consume caffeinated energy drinks.[29]

History [edit]

Energy drinks were an active subset of the early soft drink industry; Pepsi, for instance, was originally marketed as an energy booster. Coca-Cola's name was derived from its two active ingredients, both known stimulants: coca leaves and kola nuts (a source of caffeine). Fresh coca leaves were replaced by "spent" ones in 1904 because of concerns over the use of cocaine in food products; the federal lawsuit United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola and subsequent litigation pressured The Coca-Cola Company into reducing the amount of caffeine in its formula by 1916, though the Food and Drug Administration ultimately lost the case against the inanimate Coca-Cola barrels because it failed to demonstrate that the caffeine levels in the drink—78 mg per 8 fl oz, a level comparable to modern energy drinks, at the time of the lawsuit—was harmful as alleged.[30] These developments brought an end to the first wave of energy drinks.[31]

Lucozade (left) sold in Hong Kong. Created by pharmacist William Walker Hunter in the UK in 1927 it was initially marketed as an energy drink for the sick

In the UK, Lucozade Energy was originally introduced in 1927 by a Newcastle pharmacist, William Walker Hunter, as a hospital drink for "aiding the recovery;" in the early 1980s, it was promoted as an energy drink for "replenishing lost energy."[32] One of the first post-Forty Barrels energy drinks introduced in America was Dr. Enuf. Its origins date back to 1949, when a Chicago businessman named William Mark Swartz was urged by coworkers to formulate a soft drink fortified with vitamins as an alternative to sugar sodas full of empty calories. He developed an "energy booster" drink containing B vitamins, caffeine and cane sugar. After placing a notice in a trade magazine seeking a bottler, he formed a partnership with Charles Gordon of Tri-City Beverage to produce and distribute the soda.[33] Dr. Enuf is still being manufactured in Johnson City, Tennessee and sold sparsely throughout the nation.[34]

In Japan, the energy drink dates at least as far back as the early 1960s, with the launch of the Lipovitan brand. However, in Japan, most of the products of this kind bear little resemblance to soft drinks, and are sold instead in small brown glass medicine bottles, or cans styled to resemble such containers. These "eiyō dorinku" (literally, "nutritional drinks") are marketed primarily to salarymen. Bacchus-F, a South Korean drink closely modeled after Lipovitan, also appeared in the early 1960s and targets a similar demographic.[ citation needed ]

In 1985, Jolt Cola was introduced in the United States. Its marketing strategy centered on the drink's caffeine content, billing it as a means to promote wakefulness. The drink's initial slogan read: "All the sugar and twice the caffeine."[35]

In 1995, PepsiCo launched Josta, the first energy drink introduced by a major US drink company (one that had interests outside energy drinks), but Pepsi discontinued the product in 1999.[36] Pepsi would later return to the energy drink market with the AMP brand.

In Europe, energy drinks were pioneered by the Lisa company and a product named "Power Horse", before Dietrich Mateschitz, an Austrian entrepreneur, introduced the Red Bull product, a worldwide bestseller in the 21st century. Mateschitz developed Red Bull based on the Thai drink Krating Daeng, itself based on Lipovitan. Red Bull became the dominant brand in the US after its introduction in 1997, with a market share of approximately 47% in 2005.[37]

In New Zealand and Australia, the leading energy drink product in those markets, V, was introduced by Frucor Beverages. The product now represents over 60% of market in New Zealand and Australia.[38]

UK supermarkets have launched their own brands of energy drinks, sold at lower prices than the major soft drink manufacturers, that are mostly produced by Canadian beverage maker Cott. Tesco supermarkets sell "Kx" (formerly known as "Kick"), Sainsbury's sell "Blue Bolt" and Asda sell "Blue Charge"—all three drinks are sold in 250-milliliter cans and 1-liter bottles—while Morrison's sell "Source" in 250-milliliter cans. Cott sells a variety of other branded energy drinks to independent retailers in various containers.[39]

In 2002, Hansen Natural Company introduced the energy drink Monster Energy.[40] Hansen Natural Company changed their name to Monster Beverage Corporation after an agreement by shareholders to change the name after Monster Energy became the largest source of revenue.[41] The company's previous beverages were taken ownership by The Coca-Cola Company.[42]

Since 2002, there has been a growing trend for packaging energy drinks in bigger cans.[43] In many countries, including the US and Canada, there is a limitation on the maximum caffeine per serving in energy drinks, so manufacturers include a greater amount of caffeine by including multiple servings per container. Popular brands such as Red Bull, Hype Energy Drinks and Monster have increased the can size.[43]

The energy shot product, an offshoot of the energy drink, was launched in the US with products such as "5-Hour Energy," which was first released onto the market in 2004. A consumer health analyst explained in a March 2014 media article: "Energy shots took off because of energy drinks. If you're a white collar worker, you're not necessarily willing to down a big Monster energy drink, but you may drink an energy shot."[44] [45]

In 2006 energy drinks with nicotine became marketed as nicotine replacement therapy products.[46]

In 2007, energy drink powders and effervescent tablets were introduced, whereby either can be added to water to create an energy drink.[47]

Energy drinks are also popular as drink mixers—Red Bull and vodka is a popular combination. In the US, a product called "Four Loko" formerly mixed beer with caffeine, while Kahlua is a coffee-flavored alcoholic drink.[44]

On 14 August 2012, the word "energy drink" was listed for the first time in the Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary.[48]

Variants [edit]

By concentration [edit]

Energy shots [edit]

Energy shots are a specialized kind of energy drink. Whereas most energy drinks are sold in cans or bottles, energy shots are usually sold in smaller 50ml bottles.[49] Energy shots can contain the same total amount of caffeine, vitamins or other functional ingredients as their larger versions, and may be considered concentrated forms of energy drinks. The marketing of energy shots generally focuses on their convenience and availability as a low-calorie "instant" energy drink that can be taken in one swallow (or "shot"), as opposed to energy drinks that encourage users to drink an entire can, which may contain 250 calories or more.[50] A common energy shot is 5-hour Energy which contains B vitamins and caffeine in an amount similar to a cup of coffee.[51]

By ingredient [edit]

Nicotine drinks [edit]

Energy drinks with nicotine are marketed as nicotine replacement therapy products.[46]

Combined psychoactive ingredients [edit]

Caffeinated alcoholic drink [edit]

Energy drinks such as Red Bull are often used as mixers with alcoholic drinks, producing mixed drinks such as Vodka Red Bull which are similar to but stronger than rum and coke with respect to the amount of caffeine that they contain.[52] Sometimes this is configured as a bomb shot, such as the Jägerbomb or the F-Bomb — Fireball Cinnamon Whisky and Red Bull.[53]

Caffeinated alcoholic drinks are also sold in some countries in a wide variety of formulations. The American products Four Loko and Joose originally combined caffeine and alcohol before caffeinated alcoholic drinks were banned in the U.S. in 2010.[54] [55] [56]

Chemistry [edit]

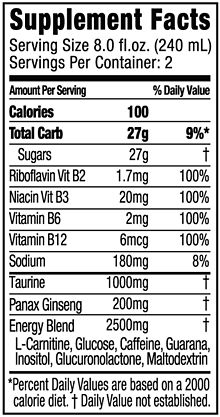

Energy drinks generally contain methylxanthines (including caffeine), B vitamins, carbonated water, and high-fructose corn syrup or sugar (for non-diet versions). Other common ingredients are guarana, yerba mate, açaí, and taurine, plus various forms of ginseng, maltodextrin, inositol, carnitine, creatine, glucuronolactone, sucralose or ginkgo biloba.[11] The sugar in non-diet energy drinks is food energy,[11] while there is no scientific evidence that addition of other ingredients has any effect on human health.

In the United States, the caffeine content of energy drinks is in the range of 40 to 250 mg per 8 fluid ounce (237 ml) serving.[57] The Food and Drug Administration recommends that 400 mg per day is safe for adults, while 1200 mg per day can be toxic.[57]

Demographics [edit]

Assorment of energy drinks displayed in a store in Bangkok

Globally, energy drinks are typically attractive to youths and young adults.[58] [59] One study revealed that the amount of caffeine being consumed was 227 milligrams per day among young adults ages 20 through 39, compared to their non-consumer counterparts, who only consumed about 52.1 milligrams of caffeine per day.[60]

Sales and trends [edit]

A Red Bull distribution truck

In 2017, global energy drink sales were about 44 billion euros.[61] The United States market for energy drinks is forecast to reach $19 billion by 2021.[59] Male consumers 18–35 years old and Hispanics were influential in growing the category through 2016.[59] In 2017, manufacturers were modifying the composition of energy drinks for reduced or no sugar content and lower calories, caffeine content, "clean" labels to reflect the use of organic ingredients, exotic flavors, and ingredients that may affect mood.[59] [61]

Regulation [edit]

This ban was challenged in the European Court of Justice in 2004 and consequently lifted.[62] Norway did not allow Red Bull for a time, although this restriction has been relaxed. In May 2009, it became legal to sell in Norway. The Norwegian version has reduced levels of vitamin B6.[63] The United Kingdom investigated the drink, but only issued a warning against its consumption by children and pregnant women.[62]

In 2009 under the Ministry of Social Protection, Colombia prohibited the sale and commercialization of energy drinks to minors under the age of 14.[64]

In November 2012, President Ramzan Kadyrov of Chechnya (Russian Federation) ordered his government to develop a bill banning the sale of energy drinks, arguing that as a form of "intoxicating drug", such drinks were "unacceptable in a Muslim society". Kadyrov cited reports of one death and 530 hospital admissions in 2012 due to "poisoning" from the consumption of such drinks. A similar view was expressed by Gennady Onishchenko, Chief Sanitary Inspector of Russia.[65]

In 2009, a school in Hove, England requested that local shops refrain from selling energy drinks to students. Headteacher Malvina Sanders added that "This was a preventative measure, as all research shows that consuming high-energy drinks can have a detrimental impact on the ability of young people to concentrate in class." The school negotiated for their local branch of the Tesco supermarket to display posters asking students not to purchase the products.[66] Similar measures were taken by a school in Oxted, England, which banned students from consuming drinks and sent letters to parents.

Some countries have certain restrictions on the sale and manufacture of energy drinks. In Australia and New Zealand, energy drinks are regulated under the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code; limiting the caffeine content of 'formulated caffeinated beverages' (energy drinks) at 320 mg/L (9.46 mg/oz) and soft-drinks at 145 mg/L (4.29 mg/oz). Mandatory caffeine labeling is issued for all food products containing guarana in the country,[67] and Australian energy drink labels warn consumers to drink no more than two cans per day.[68]

As of 2013 in the United States some energy drinks, including Monster Energy and Rockstar Energy, were reported to be rebranding their products as drinks rather than as dietary supplements. As drinks they would be relieved of F.D.A. reporting requirements with respect to deaths and injuries and can be purchased with food stamps, but must list ingredients on the can.[69]

In November 2014, Lithuania became the first country in the EU to ban the selling of energy drinks to anyone under the age of 18. The Baltic state placed the ban in reaction to research showing how popular energy drinks were among minors. According to the AFP reports roughly 10% of school-aged Lithuanians say they consume energy drinks at least once a week.[70]

In June 2016, Latvia banned the sale of energy drinks containing caffeine or stimulants like taurine and guarana to people under the age of 18.[71] In January 2018, many United Kingdom supermarkets banned the sale of energy drinks containing more than 150 mg of caffeine per liter to people under 16 years old;[72] this was followed by the UK government banning all sales of energy drinks to minors in 2019.[73]

Ban on caffeinated alcoholic drinks [edit]

Some places ban the sale of prepackaged caffeinated alcoholic drinks, which can be described as energy drinks containing alcohol. In response to these bans, the marketers can change the formula of their products.[74]

See also [edit]

- List of energy drinks

- Sport drink

- Elixir

- Soft drink

- Caffeinated alcoholic drinks

References [edit]

- ^ Preszler, Buss. "How much is too much?". mayoclinic.org. Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ a b c "Scientific Opinion on the safety of caffeine". EFSA Journal. 13 (5). May 2015. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4102.

- ^ a b McLellan TM, Lieberman HR (2012). "Do energy drinks contain active components other than caffeine?". Nutr Rev. 70 (12): 730–44. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00525.x. PMID 23206286.

- ^ a b Van Den Eynde F, Van Baelen PC, Portzky M, Audenaert K (2008). "The effects of energy drinks on cognitive performance". Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie. 50 (5): 273–81. PMID 18470842.

- ^ Alford, C.; Cox, H.; Wescott, R. (1 January 2001). "The effects of red bull energy drink on human performance and mood". Amino Acids. 21 (2): 139–150. doi:10.1007/s007260170021. PMID 11665810. S2CID 25358429.

- ^ a b Mora-Rodriguez R, Pallarés JG (2014). "Performance outcomes and unwanted side effects associated with energy drinks". Nutr Rev. 72 Suppl 1: 108–20. doi:10.1111/nure.12132. PMID 25293550.

- ^ a b c Reissig CJ, Strain EC, Griffiths RR (2009). "Caffeinated energy drinks—a growing problem". Drug Alcohol Depend. 99 (1–3): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.001. PMC2735818. PMID 18809264.

- ^ a b Sanchis-Gomar F, Pareja-Galeano H, Cervellin G, Lippi G, Earnest CP (2015). "Energy drink overconsumption in adolescents: implications for arrhythmias and other cardiovascular events". Can J Cardiol. 31 (5): 572–5. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2014.12.019. hdl:11268/3906. PMID 25818530.

- ^ a b Petit A, Karila L, Lejoyeux M (2015). "[Abuse of energy drinks: does it pose a risk?]". Presse Med. 44 (3): 261–70. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2014.07.029. PMID 25622514.

- ^ Higgins, John; Yarlagadda, Santi; Yang, Benjamin; Higgins, John P.; Yarlagadda, Santi; Yang, Benjamin (June 2015). "Cardiovascular Complications of Energy Drinks". Beverages. 1 (2): 104–126. doi:10.3390/beverages1020104.

- ^ a b c d e f g Meier, Barry (1 January 2013). "Energy Drinks Promise Edge, but Experts Say Proof Is Scant". The New York Times. New York. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ a b O'Brien, Mary Claire; McCoy, Thomas P.; Rhodes, Scott D.; Wagoner, Ashley; Wolfson, Mark (2008). "Caffeinated Cocktails: Energy Drink Consumption". Academic Emergency Medicine. 15 (5): 453–60. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00085.x. PMID 18439201.

- ^ EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (2011). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims from Energy Drinks". EFSA Journal. 9 (4): 2035 [19 pp.] doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2035. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims". EFSA Journal. 8 (10): 1756. 2010. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1756. Archived from the original on 13 November 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "Red Bull Gives You Wings - RedBull.com". Red Bull. 2004.

- ^ Plamondon, Laurie (2013). "Energy Drinks: Threatening or Commonplace? An Update" (PDF). TOPO (6): 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ Nathan, PJ; Lu, K; Gray, M; Oliver, C (20 April 2015). "The neuropharmacology of L-theanine(N-ethyl-L-glutamine): a possible neuroprotective and cognitive enhancing agent". J Herb Pharmacother. 6 (2): 21–30. doi:10.1300/J157v06n02_02. PMID 17182482.

- ^ Williams JL, Everett JM, D'Cunha NM, Sergi D, Georgousopoulou EN, Keegan RJ; et al. (2020). "The Effects of Green Tea Amino Acid L-Theanine Consumption on the Ability to Manage Stress and Anxiety Levels: a Systematic Review". Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 75 (1): 12–23. doi:10.1007/s11130-019-00771-5. PMID 31758301.

The supplementation of L-THE in its pure form at dosages between 200 and 400 mg/day may help reduce stress and anxiety acutely in people undergoing acute stressful situations, but there is insufficient evidence to suggest it assists in the reduction of stress levels in people with chronic conditions. However, the results of this study suggest that L-THE taken during times of heightened acute stress or by individuals with a high propensity for anxiety and stress may exhibit beneficial properties via the increased production of alpha waves and decrease of glutamate in the brain.

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Winston AP (2005). "Neuropsychiatric effects of caffeine". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 11 (6): 432–439. doi:10.1192/apt.11.6.432.

- ^ Warning: Energy Drinks Contain Caffeine Archived 7 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine by Allison Aubrey. Morning Edition, National Public Radio, 24 September 2008.

- ^ a b Pennay A, Lubman DI, Miller P (2011). "Combining energy drinks and alcohol" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ O'Brien MC, McCoy TP, Rhodes SD, Wagoner A, Wolfson M (2008). "Caffeinated cocktails: Energy drink consumption, high-risk drinking, and alcohol-related consequences among college students". Academic Emergency Medicine. 15 (5): 453–60. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00085.x. PMID 18439201.

- ^ a b c d Al-Shaar, Laila; Vercammen, Kelsey; Lu, Chang; Richardson, Scott; Tamez, Martha; Mattei, Josiemer (31 August 2017). "Health Effects and Public Health Concerns of Energy Drink Consumption in the United States: A Mini-Review". Frontiers in Public Health. 5: 225. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2017.00225. ISSN 2296-2565. PMC5583516. PMID 28913331.

- ^ "What About Energy Drinks for Kids?". Stanford Children's Health, Stanford University. 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Clauson KA, Shields KM, McQueen CE, Persad N (2008). "Safety issues associated with commercially available energy drinks". J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 48 (3): e55–63, quiz e64–7. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07055. PMID 18595815.

- ^ Emily A. Fletcher; Carolyn S. Lacey; Melenie Aaron; Mark Kolasa; Andrew Occiano; Sachin A. Shah (May 2017). "Randomized Controlled Trial of High‐Volume Energy Drink Versus Caffeine Consumption on ECG and Hemodynamic Parameters". Journal of the American Heart Association. 6 (5): e004448. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.004448. PMC5524057. PMID 28446495.

- ^ a b c d "The DAWN Report: Update on Emergency Department Visits Involving Energy Drinks: A Continuing Public Health Concern". archive.samhsa.gov. Archived from the original on 17 February 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (10 January 2013). "Update on Emergency Department Visits Involving Energy Drinks: A Continuing Public Health Concern" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ "Kids Should Not Consume Energy Drinks, and Rarely Need Sports Drinks, Says AAP". American Academy of Pediatrics. 30 May 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ United States v. Forty Barrels & Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola, 241 U.S. 265 (1916).

- ^ Ronald Hamowy (2007), Government and public health in America (illustrated ed.), Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 140–141, ISBN978-1-84542-911-9

- ^ "We did it first". The Northern Echo. 1 September 2021.

- ^ Fred W. Sauceman (1 March 2009). The Place Setting: Timeless Tastes of the Mountain South, from Bright Hope to Frog Level. Mercer University Press. pp. 89–. ISBN978-0-88146-140-4.

- ^ Saxena, Jaya. "How Energy Drinks Through the Ages Have Gotten Humanity JACKED UP". Pictorial. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ About Jolt Energy Drink. joltenergy.com

- ^ "PepsiCo to Stop Selling Josta Brand". Los Angeles Times. 26 March 1999. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ "Soda With Buzz". Forbes, Kerry A. Dolan. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2005.

- ^ "Our brands – V". Frucor. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "Cott Announces Agreement to Sell Its Traditional Beverage Manufacturing Business to Refresco in All-Cash Transaction". Cott Corporation . Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "What's Hot: Hansen Natural". April 2002. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ "New Stock Ticker Press release" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ "Coke Takes Ownership of Monster's Non-Energy Business". Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Energy Drinks: Boost in Action Ahead". Food Directions. 25 January 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ a b Roberto A. Ferdman (26 March 2014). "The American energy drink craze in two highly caffeinated charts". Quartz. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ O'Connor, Clare (8 February 2012). "The Mystery Monk Making Billions With 5-Hour Energy". Forbes. Forbes LLC. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ a b "Nicotine Drink Touts Alternative to Smoking". ABC News.

- ^ "Caffeine Experts at Johns Hopkins Call for Warning Labels for Energy Drinks - 09/24/2008". Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ Italie, Leanne. "F-bomb makes it into mainstream dictionary". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Miller, Kevin (1 February 2017). "As more 'nips' bottles litter Maine landscape, group calls for 15-cent deposit". Portland Press Herald. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ Klineman, Jeffrey (30 April 2008). ""Little competition: energy shots aim for big" profits". Bevnet.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "What's In A 5-hour ENERGY Shot?". 5-hour ENERGY. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT, Bardgett ME, Howard MA (2011). "Effects of energy drinks mixed with alcohol on behavioral control: Risks for college students consuming trendy cocktails". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 35 (7): 1282–92. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01464.x. PMC3117195. PMID 21676002.

- ^ Hoare, Peter (9 January 2014). "5 Awesome Drinks You Can Make With Fireball Cinnamon Whisky". Food & drinks. MTV. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ FDA (3 November 2010). "List of Manufacturers of Caffeinated Alcoholic Beverages". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Zezima, Katie (26 October 2010). "A Mix Attractive to Students and Partygoers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Bruni, Frank (30 October 2010). "Caffeine and Alcohol: Wham! Bam! Boozled". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Spilling the beans: How much caffeine is too much?". US Food and Drug Administration. 12 December 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Visram, Shelina; Crossley, Stephen J.; Cheetham, Mandy; Lake, Amelia (31 May 2016). "Children and young people's perceptions of energy drinks: A qualitative study". PLOS ONE. 12 (11): e0188668. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188668. PMC5708842. PMID 29190753.

- ^ a b c d Martin Caballero (18 May 2018). "Energy's Evolution: It's a huge category. But where do energy drinks go next?". Bevnet. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ Vercammen, Kelsey A.; Koma, J. Wyatt; Bleich, Sara N. (1 June 2019). "Trends in energy drink consumption among U.S. adolescents and adults, 2003-2016". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 56 (6): 827–833. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.12.007. PMID 31005465.

- ^ a b "Energy Drink Sales Still on the Rise, Despite Slowdown in Innovation". Nutritional Outlook. 28 June 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ a b "French ban on Red Bull (drink) upheld by European Court". Medicalnewstoday.com. 8 February 2004. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ^ Red Bull blir tillatt i Norge – NRK Norge – Oversikt over nyheter fra ulike deler av landet Archived 21 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Nrk.no (23 April 2009). Retrieved on 2016-11-14.

- ^ RESOLUCION 4150 DE 2009 (octubre 30). Diario Oficial No. 47.522 de 3 de noviembre de 20 Archived 3 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. invima.gov.co

- ^ "Kadyrov Vows to Ban Energy Drinks". The Moscow Times. 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ "Pupils facing energy drink 'ban'". BBC News. 7 October 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ^ "Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code – Standard 2.6.4 – Formulated Caffeinated Beverages – F2009C00814". comlaw.gov.au. Department of Health and Ageing (Australia). 13 August 2009. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Pogson, Jenny (9 May 2012). "Energy drinks pack more punch than you might expect". ABC. Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ^ Barry Meier (19 March 2013). "In a New Aisle, Energy Drinks Sidestep Some Rules". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ "A Country In Europe Bans Energy Drinks For Minors". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ Latvia bans sales of energy drinks to under-18s Archived 15 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press. June 1, 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2017

- ^ Smithers, Rebecca (5 March 2018). "UK supermarkets ban sales of energy drinks to under-16s". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Deutrom, Rhian; Newton Dunn, Tom (17 July 2019). "UK Government to ban the sale of energy drinks to minors". ABC News . Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ "Four Loko Changing Its Formula". NBC Chicago. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

Further reading [edit]

- Bagchi, D. (2017). "Chapter 26: Caffeine-Containing Energy Drinks/Shots: Safety, Efficacy and Controversy". Sustained Energy for Enhanced Human Functions and Activity. Elsevier Science. pp. 423–445. ISBN978-0-12-809332-0 . Retrieved 23 October 2018.

External links [edit]

- Sport and Energy drinks at Curlie

- USA Today-Overuse of Energy drinks...

- Teens Who Consume Energy Drinks Are at Higher Risk for Drug Use

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_drink